Dr Davey Smith was munching on popcorn, trying to enjoy a quiet lunch break two days after Thanksgiving, when an email opened on his iPad with news that filled him with deep terror. and dark.

UC San Diego’s infectious disease chief was learning from his colleagues in South Africa that Omicron, the new strain of COVID-19 discovered there, could be a real troublemaker.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Days earlier, Smith believed he had simply found a contaminated sample, and not a clever successor to COVID-19 and the Delta variant. New data has proven otherwise. A new threat had arisen.

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, could that be COVID 3.0? â€Smith said. “Will the vaccines work against this?” Will our drugs be effective? We need these tools. This is not where we wanted to come from.

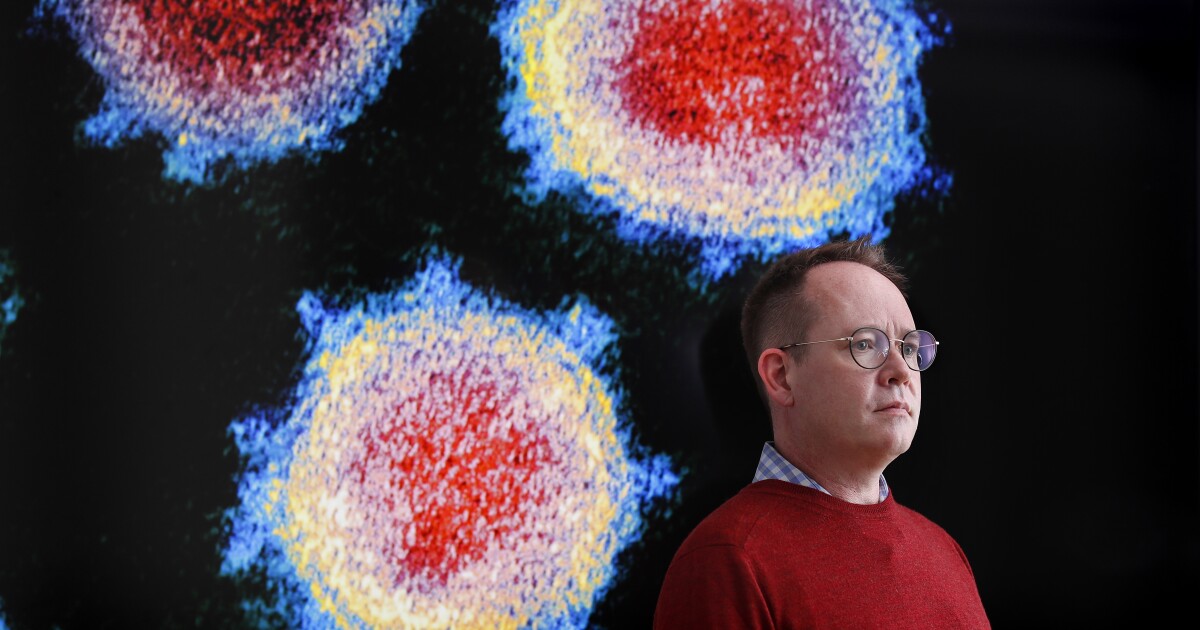

Smith is at the forefront of a race of scientists at UCSD and elsewhere to answer these and other questions that could determine whether the world falls back into another pandemic year.

The news about Omicron was surprising and disturbing, but not surprising for Smith, a 50-year-old medical researcher who is conducting clinical trials on drugs designed to fight COVID-19, including tests currently underway in South Africa. .

Viruses mutate. This is a defining characteristic. You must follow.

Research associate Brendon Woodworth performed a test on swab samples for COVID at the UC San Diego Infectious Disease Research Lab on Thursday, December 2, 2021.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

But the news hit the audience like a punch.

There has been a general feeling in recent months that the pandemic is fading, even though many refuse to be vaccinated. Airlines carried 2.3 million passengers over Thanksgiving, a number almost as high as before the trouble began.

But the post-Thanksgiving mood is one of great distrust among the public and among scientists who are suddenly back on the war footing with an enemy who has killed 5.23 million people worldwide.

The researchers said that Omicron, which is smaller than a dust particle, will quickly spread around the world. And he did.

The first case in the United States was reported in San Francisco on Wednesday. It was about a vaccinated man who had recently traveled to South Africa. The next day, more cases emerged in California in other parts of the country. At the end of the week, new reports were reported in South Africa that Omicron can more easily cause reinfection and can spread much faster than even the highly infectious Delta variant.

No one had immediate answers, including immunologist Kristian Anderson of Scripps Research, one of San Diego’s most respected life scientists.

His Twitter feed on Tuesday carried a deflating message: “Omicron – on a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is it going to be? This one’s a weirdo, so I’m a 3, a 10, or whatever in between.

Scientists will soon have partial answers – and, in a cruel twist, they will likely arrive around Christmas and New Years.

In science centers like San Diego, researchers are trying to determine whether Omicron has a potent ability to overwhelm a vaccine’s defenses and cause infections and disease. They do this by taking blood samples from vaccinated people and those who have recently recovered from COVID-19 and exposing them to the new virus.

Scientists are able to use a synthetic version of Omicron – a pseudovirus that contains all of the approximately 50 variant mutations. The technique gives results in about 10 days.

Researchers like Smith are also trying to obtain real versions of the variant. He has spent much of the past week trying to get officials in South Africa and the United States to speed things up.

Scientists fear that Omicron will crush the antibodies that help keep people from getting infected. On the positive side, many believe that another key part of the immune system, T cells, will vigorously fight the disease caused by the virus. These cells determine a specific course of action to fight against foreign substances and help to wage war.

That’s why researchers are relentlessly pushing vaccines and boosters.

Scientists like Smith are using a similar blood-based approach to determine whether Omicron will neutralize monoclonal antibodies that are part of some new therapeutic drugs.

The researchers are also examining the genetic makeup of Omicron, which has 50 mutations, many more than the dominant strain Delta. We do not yet know exactly what each of the mutations does, alone or in concert. And some of the mutations are new to science. But there are some early ideas.

Alessandro Sette, Institute of Immunology of La Jolla

(Courtesy of La Jolla Institute of Immunology)

“Based on the mutations observed, pretty much everyone predicts that the antibody response produced by (the vaccines) will be reduced,” said Alessandro Sette, researcher at the La Jolla Institute of Immunology.

“The question is will this also be the case for the T cell response?” ”

The concern is that Omicron might, in a way, also weaken the counterattack launched by T cells.

Scientists have publicly pointed out that they were only thinking of Omicron and that the strain may be less threatening than it looks. And Sette noted that the problems caused by the virus could be offset with booster shots.

Despite this, Smith’s mind drifted into dark territory Tuesday during an interview with the Union-Tribune. He brought up the “L†word, something no one wants to hear.

“I don’t know if this will lead to a lockdown, but there’s a chance we could come back to the bad times,†said Smith, a straightforward, outspoken man whose words have a lyricism that reflects his upbringing in Tennessee. “I don’t think we’ll come to that. But that’s what worries me. “

He also said he could imagine a scenario in which US universities would have to put some of their courses back online if Omicron became a major problem.

He realizes that such remarks can annoy people; he shrugged, saying, “The virus doesn’t care about politics, and neither should science.”

His comments about the universities caused some stir at UC San Diego, which has been hailed over the past 18 months for producing one of the lowest campus infection rates in the country while simultaneously helping to develop COVID-19 vaccines and drugs and to inoculate hundreds of thousands of people.

The school opened with a record 42,875 students in September and, like other institutions, is unwilling to back down.

“You don’t go from ‘there’s a new variant in South Africa’ to ‘don’t come back to campus after Christmas’,†said Dr Robert Schooley, the infectious disease expert who led the Return program to Learn from UCSD, the protocols used to open the school safely.

“We’re about as well prepared for this as we have been for anything,†he said.

As he spoke, UCSD collected sewage samples on campus in its daily search for traces of coronavirus. The monitoring program was introduced last year and now includes Omicron research.

Postdoctoral researcher Smruthi Karthikeyan collects a waste sample from one of 131 on-campus autosamplers that monitor 350 campus buildings on Friday, December 3, 2021.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Schooley is a strong supporter of Smith, who for years was one of the best-known HIV researchers in the United States. He’s a doctor too – someone who knows that positive change can happen quickly.

In July 1996, he started using the famous HIV drug cocktails that Schooley, a researcher, helped develop. Smith quickly switched from monitoring patients to dying to recover sufficiently to leave the hospital.

“The things we’ve learned from studying HIV set everything we do with COVID into place,†Smith said.

Shortly after the start of the pandemic, Smith became a member of Operation Warp Speed, the public-private partnership created by the Trump administration to develop vaccines, drugs and diagnostics to fight COVID-19.

He began to lead ACTIV-2, a major clinical trial to test the safety and effectiveness of new therapies. This work and others have made him part of the inner circle of science.

Smith typically begins his days from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m. on conference calls with members of the NIH, including Dr.Anthony Fauci. He keeps his Zoom camera dark so he can work out on the elliptical machine at his home in Mission Hills.

Research associate Gemma Cabellero examined a sample of cDNA infected with COVID at the UC San Diego Infectious Disease Research Lab on Thursday, December 2, 2021.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Meetings have taken on a heavy tone in recent days, a mood that contrasts with Smith’s normally sunny disposition.

“He’s the most optimistic person I’ve ever met,” said Dr. Susan Little, an infectious disease expert at UCSD and a physician who conducts separate COVID vaccine trials on behalf of AstraZeneca and Janssen.

“He has a unique ability to see the good in everyone, the silver lining, to be patient and compassionate.”

Those traits were being tested on Friday as Smith boarded a plane for a science meeting in Mexico. There was news from South Africa that Omicron had become the dominant COVID strain in some provinces.

“I think we’re in as bad a situation as last year (at) this time,” Smith said via text as he headed south. “It looks like the end of winter could be difficult.

“I hope the vaccine holds up (and) helps prevent people from needing to be hospitalized.”

The New York Times contributed to this story.